This article was scraped from Rochester Subway. This is a blog about Rochester history and urbanism has not been published since 2017. The current owners are now publishing link spam which made me want to preserve this history.. The original article was published January 15, 2012 and can be found here.

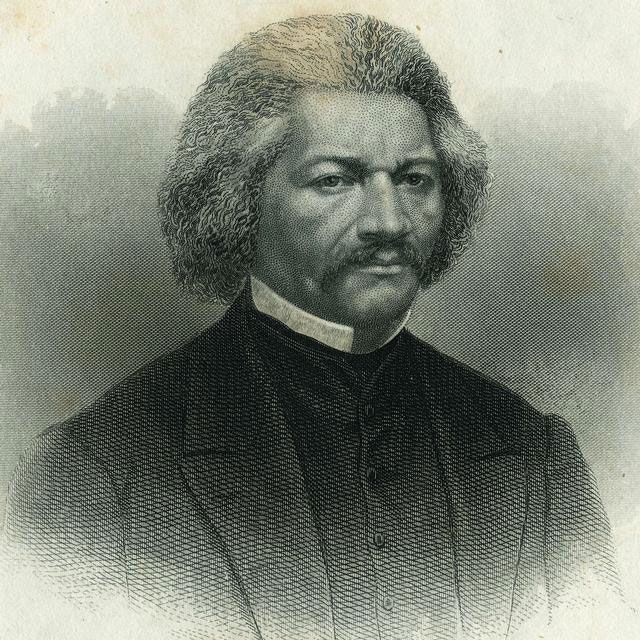

![An engraved portrait of Frederick Douglass, noted African-American abolitionist. Douglass was an active abolitionist in the Rochester area and a sought-after lecturer after the Civil War. After his home on South Avenue was destroyed by fire in 1872 he moved to Washington, D.C. [PORTRAIT BY: Ritchie, Alexander Hay, 1822-1895.]](https://senseofplace.dev/content/images/photos/frederick-douglass-portrait.jpg)

On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day we are hopefully reminded of the inspiring actions and many speeches by an individual who dedicated his life to the pursuit of freedom and basic human rights--not just for one group, but for all people.

Of course, in Rochester we also remember other individuals who made tremendous contributions to this ongoing effort... Susan B. Anthony for women's rights and suffrage. And Frederick Douglas (depicted above) for the abolition of slavery.

One speech in particular, given by Douglas on July 5, 1852 in Rochester, is arguably one of the most momentous oratories in American history. It's one that helped set the stage for the transformation of America from a country that was, in Abraham Lincoln's words, "half slave and half free" to one which was at least on its way to guaranteeing the "blessings of liberty" to all men (and eventually women)...

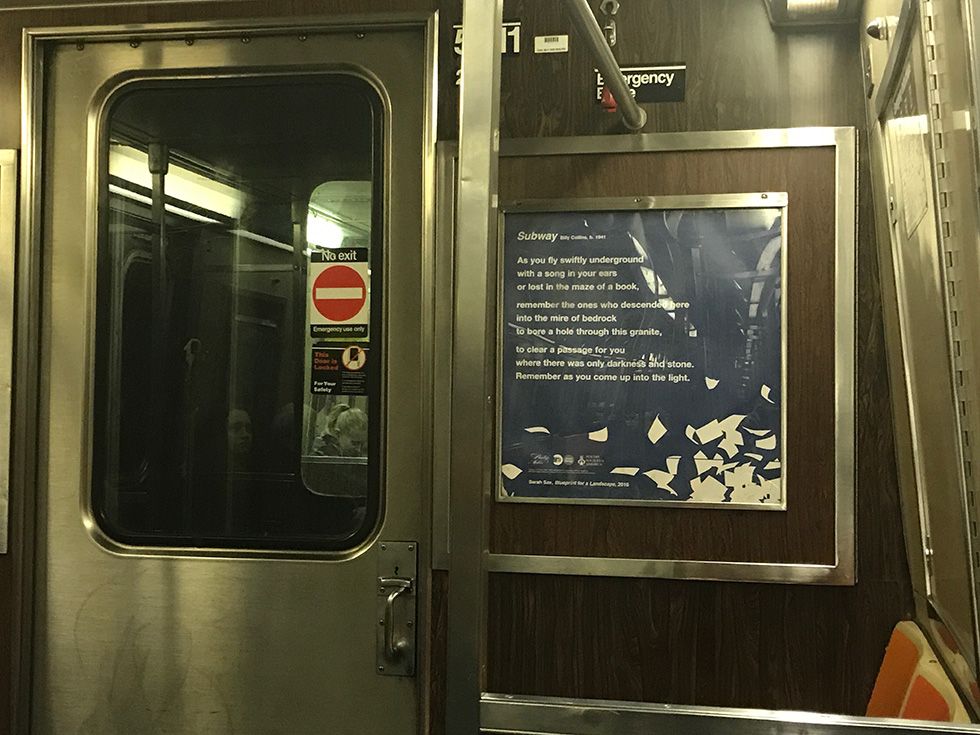

Douglass' address was delivered at Corinthian Hall

, one of Rochester's most prestigous sites for concerts, balls, lectures, fairs, plays and parties. The great hall stood on what is now called Corinthian Street

, behind Reynold's Arcade (unfortunately the building was razed in 1928 and replaced with a parking area). The event was hosted by the Ladies of the Rochester Anti Slavery Sewing Society

to commemorate the signing of the Declaration of Independence; and the irony was not lost on Douglass. He told his audience: This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

On the surface Douglass' oratory was a blistering attack on the hypocrisy of slavery in the United States and eventually became known as What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?

But his message went much deeper by challenging the widely-held belief (among white and even black freemen) that the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slave document... Fellow-citizens! there is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon, as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither. While I do not intend to argue this question on the present occasion, let me ask, if it be not somewhat singular that, if the Constitution were intended to be, by its framers and adopters, a slave-holding instrument, why neither slavery, slaveholding, nor slave can anywhere be found in it. What would be thought of an instrument, drawn up, legally drawn up, for the purpose of entitling the city of Rochester to a track of land, in which no mention of land was made?

Douglass, and others later on, would argue that the Constitution could, and should, be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.

![A view of the home of Isaac and Amy Post, a stop on the Underground Railroad (1893). It was located on Sophia Street (now Plymouth Avenue) in Rochester. The site later became Central Presbyterian Church where the funerals of Frederick Douglass (1895) and Susan B. Anthony (1906) took place. Today the church is used by Hochstein Music School. [IMAGE: Rochester Public Library]](https://senseofplace.dev/content/images/photos/post-house-underground-railroad-rochester.jpg)

Frederick Douglass wrote several books

about his life detailing his escape by train from slavery in Baltimore, and also his work in Rochester, where he often hid other people who were escaping to Canada. This house on Sophia Street (now Plymouth Ave.) was one local stop on the Underground Railroad.

The hardships Douglass had to overcome to be able to speak on this stage in Rochester were astounding. Born into slavery, separated from his mother as an infant, traded like property, beat down physically and psychologically by several 'masters', denied any meaningful education, stripped of his identity... he never even knew his own age! In spite of all this, somehow he could see ahead to a day when America would fulfill its promise:

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.

![LEFT: A view showing the laying of the cornerstone of the monument to Frederick Douglass in Rochester. The ceremony took place on July 20, 1898 and was attended by hundreds of citizens. [IMAGE: Rochester Public Library] ... RIGHT: The Frederick Douglass monument, made by Sidney W. Edwards, was first unveiled in 1899, facing south, at Central Avenue and St. Paul Street. The New York Central Railroad Station is in the background. It was later moved to Highland Park and rededicated, September 4, 1941. It now faces north. [IMAGE: Albert R. Stone Collection]](https://senseofplace.dev/content/images/photos/frederick-douglass-monument-rochester.jpg)

And with that last line, spoke 160 years ago in Rochester NY, Frederick Douglass delivered the type of forward-looking message of hope that would be heard in the inspiring words of Martin Luther King Jr. one hundred and ten years later; and one day echoed by America's first black president.